By Tracy Murnan Stackhouse and Sarah K. Scharfenaker

Therapy is a fun, creative process — one of the reasons that we have been at this for so long!

One of the challenges of being a therapist is staying on top of the ever-emerging intervention techniques that come into practice. Not only is it important to know the best strategies available, but it is important to carefully analyze each technique for its utility and efficacy. As most strategies are typically devised or targeted at a population other than those with Fragile X syndrome (FXS), we have taken it upon ourselves to always analyze the strategies in light of the FXS learning style. Most often we find it necessary to modify even the most researched interventions to work for individuals with FXS.

One strategy that we have found particularly applicable comes from the arena of positive behavioral support — video modeling. Video modeling has been studied primarily for use with individuals with autism spectrum disorders. (See suggested reading at the end of the article).

Video modeling capitalizes on several characteristics we appreciate in individuals with FXS. They are strong visual learners and imitators, and they have enjoyment and love for the dramatic. Video modeling utilizes readily available technology to provide a model of appropriate social, language, behavior, or specific targeted daily living or job skills. The model can be the individual themselves or a peer or adult chosen for the individual’s interest in them. Since the model is on video, the individual with FXS can view the model multiple times in different settings. This offers multiple opportunities to learn and understand the new behavior or skill.

The typical procedure used for video modeling is outlined below. Following that we review several case studies of the successful use of video modeling from our own clinical work.

Procedure

The first task in the successful implementation of this strategy is to determine the targeted skill, or behavior, that needs to be addressed. As noted above, you may want to use this strategy to change a behavior, learn a new skill, or decrease anxiety. The applications are as broad as your imagination!

Once you determine your purpose, choose a highly motivating person or situation to video, while they demonstrate the skills you are targeting. It is very important to plan out exactly what you want the video to convey. Provide your “actor” with scripts and cues that will guide them and that will be meaningful for the person for whom the video is intended. Finally, you are ready to create the video. Most video cameras are easy to use and allow you to film without having to worry about lighting, editing, etc. Relax and have fun creating your video model masterpiece!

Once the video is made, the individual needs multiple opportunities to watch it.

Sometimes we have the person watch it at home several times before introducing the real situation. Sometimes we view it in the clinic and immediately create an opportunity to put the new skill into action. Sometimes we role-play, or create opportunities for in-vivo practice, in conjunction with the video model.

Finally, we have come to find that videotaping the individual successfully performing the new skill as a follow-up video is a wonderful way to reinforce learning.

The video model should be used until the child has mastered the new task or behavior and keeping the video in a library for future use may also come in handy.

Case Studies

9-Year-Old

We first used video modeling to help a nine-year-old boy, whom we’ll call Mannie, learn more appropriate greeting behaviors. When in a store, he would greet his mother’s friends by running up and tickling them and yelling, “I’m gonna get you!”

We developed a plan to utilize many of Mannie’s favorite people greeting others in appropriate ways, using language such as, “Hi, how are you doing?” or “Hi, can I have a high five?” These people were videotaped using these simple greetings and appropriate responses in a variety of familiar settings that Mannie often encountered, including Safeway, Tower Records, and Best Buy. After the video was filmed, we spent one therapy session with Mannie discussing its content and watching it. Immediately after the first viewing, one of the people in the video knocked on the door of the therapy room and entered. Mannie immediately used the appropriate greeting that had just been modeled in the video. His correct response was videotaped as well and shown to him for reinforcement. The videos were sent home for him to watch at home and practice with his family.

We have also found that video modeling can be used to reduce anxiety by making a new situation less novel.

High Schooler

Jim is a high schooler about to embark on his first work experience at the local hardware store. Jim can be somewhat aggressive if not prepared for novel experiences. He is also minimally verbal. At school, his teachers were trying to prepare him for this new vocational experience but using words to describe what was going to happen was not meaningful for Jim. He didn’t even understand the concept of what work or a job was.

In this instance, a video was made to introduce the idea of work. It featured important people in his life doing their jobs and working. These people included his favorite teachers and his parents. Additionally, restaurant workers behind the counter at McDonald’s were also featured. The video was narrated in very simple language, describing how everyone works. Everyone has a job. The people at McDonald’s work. They make hamburgers. Mr. Lucero works because he teaches the kids in Jimmy’s class. After a brief description and example of people and work, a video of the hardware store where Jim was to work was featured. The front of the store and the area where he was to work was also filmed. The narration then moved on to describe that “Jim is going to work; he will work at Ace Hardware. He will work with the nails and with the white pipe.” Follow-up tapes of the actual work tasks would be an appropriate way to use a series of video models to positively support a new situation such as Jimmy’s new job.

Elementary Student

Another elementary student we worked with loved video modeling so much that he has had over 10 videos created to help him learn everything from toileting to increasing the range of foods eaten to participating in PE class to finishing worksheets independently at school. For the toileting task, everything was videotaped, from going into the room to clothing management to actually getting the mechanics of going in the toilet down to washing his hands at completion.

The filming of this “private” behavior took some creative camera angles, but it really allowed this boy to make the associations necessary to understand the whole toileting idea and process. It also highlighted the FXS learning style.

Prior to the video modeling intervention, each of the pieces of the toileting process had previously been taught as individual segments. However, this boy could not put the pieces together into a meaningful “whole” so he had not been able to learn from the segmental, discrete teaching process. In contrast, the video model presents the task in its entirety, thus, the sequential processing and instruction are minimized allowing for the gestalt of the process to be conveyed, thus allowing for optimal learning. This method leads to his acquisition of the skill after only two attempts following several viewings of the tape. He generalized the skill right away, successfully toileting at home, school, and even at a public venue all within the first two weeks of learning how.

As the cases illustrate, video modeling can assist in the acquisition, or improvement, of a variety of social or language skills for a specific job or daily living skill. The method requires upfront planning and time to create a proper model, but in the end, is a valuable tool. We have found most of the individuals with FXS love watching the tapes, and their emulation of the model comes readily when the real situation arises. It has proven to be a wonderful tool for skill acquisition and generalization. We plan to continue to use video modeling for multiple clinical issues and love the creative process of implementing this powerhouse strategy.

Suggested Reading

Video Modeling: Why Does it Work With Autism? — Corbett, B.A., Abdullah, M. (2005)

Effects of Video Modeling on Social Initiations by Children With Autism — Nikopoulos, C.A., Keenan, M. (2004)

Video Modeling: A window Into the World of Autism — Corbett, B. A. (2003)

A Comparison of Video Modeling With In-Vivo Modeling for Teaching Children with Autism — Charlop-Christy, M.H., Lod Le, Freeman, K.A. (2000)

Do-Watch-Listen-Say: Social and Communication Intervention for Children with Autism — Quill, K.A. (2000)

author

Tracy Murnan Stackhouse, MA, OTR

Tracy Murnan Stackhouse is the co-founder of Developmental FX in Denver. She is a leading pediatric occupational therapist involved in clinical treatment, research, mentoring, and training regarding OT intervention for persons with neurodevelopmental disorders, especially Fragile X syndrome and autism. Tracy teaches nationally and internationally on sensory integration, autism, and Fragile X. Tracy is a member of the National Fragile X Foundation Clinical Research Consortium (FXCRC), the FXCRC Advisory Council, and the Scientific & Clinical Advisory Committee.

author

Sarah K. Scharfenaker, MA, CCC-SLP

Sarah K. Scharfenaker, fondly known as “Mouse,” is the now-retired co-founder of Developmental FX. She has worked in the fields of Fragile X syndrome and neurodevelopmental disorders for more than 25 years. She provided speech pathology services to the Denver Fragile X Treatment and Research Center at The Children’s Hospital in Denver, and accompanied Dr. Randi Hagerman to the UC Davis MIND Institute to initiate its program. She has a master’s in speech pathology from the University of Montana.

learn more

Multidisciplinary Treatment of Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) — Webinar

Drs. Craig Erickson, Laura Hess, Kerrie Chitwood, and Rebecca Shaffer joined us for a one-hour Q & A discussing the benefits of a multidisciplinary team.

Increasing Access to Services for Families of Infants with Fragile X — Webinar Replay

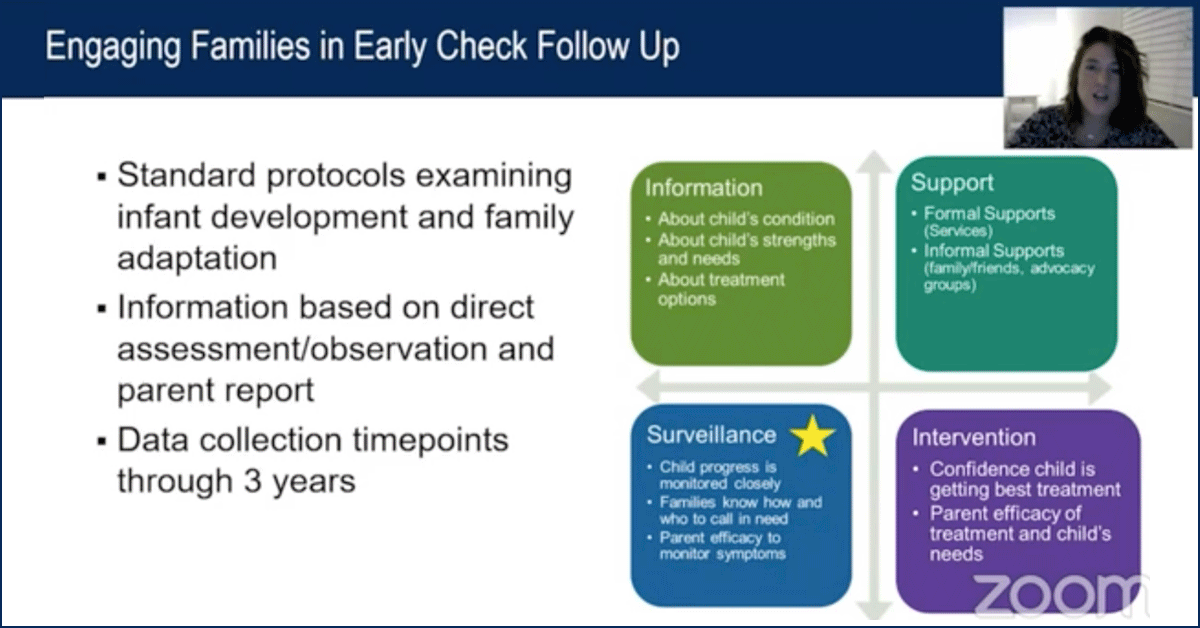

Hear an overview of how the Early Check team integrates telehealth models to provide families with the necessary information, support, surveillance, and intervention.