No one will stop you from getting genetic testing, but there are many reasons it might not happen.

If a child is diagnosed with autism, and any of its associated genetic disorders runs in your family, the doctor may recommend further genetic testing. However, a woman (and her doctor) with a known family history of Fragile X would already be aware of the need for testing, with or without an autism diagnosis.

So, what about the mother or father who isn’t aware of a genetic disorder lurking in their family history?

We looked into this and found two issues potentially hindering the convergence of an autism diagnosis with a known genetic cause. One is lack of consensus and the other is the test itself, meaning:

- Lack of Consensus: There is no solidarity on whether or not to recommend genetic testing

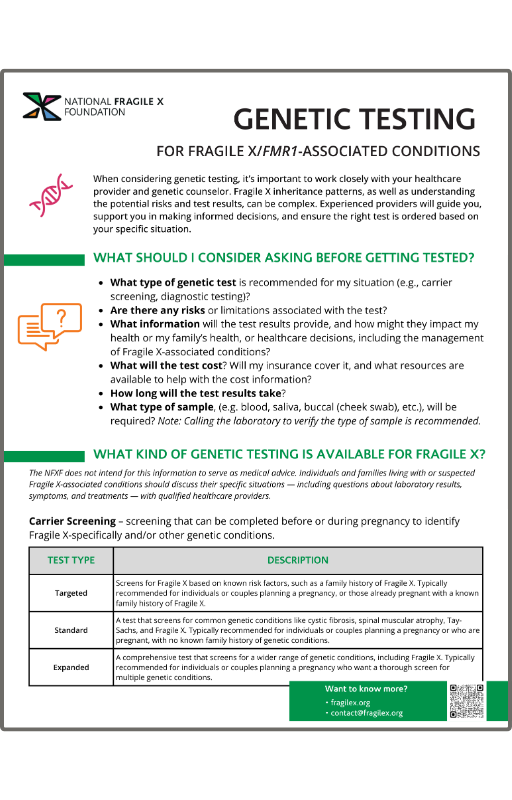

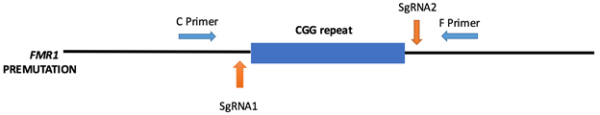

- Which Genetic Test: If testing is ordered, will it include the FMR1 gene (or any specific gene for that matter).

1. Lack of Consensus

One lab we looked at during our research reported that the most common question they received from parents when offered genetic testing following an autism diagnosis is: Why get a genetic test if my child has already been diagnosed?

And that’s just the start of the confusion families go through with any complicated medical or behavioral diagnosis. The ensuing flood of information is overwhelming (e.g., we built an entire website around navigating your way through Fragile X), and most will need some level of guidance as they sift through it all so they can make informed decisions around their future care.

A recent study — Pathways from Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Diagnosis to Genetic Testing — looked at the experiences of families and their health providers as they moved from diagnosis, to the offer of genetic testing to determine etiology, to the decision of whether to pursue testing. Some of what they found includes:

- Many providers choose not to offer testing to families and many families are unaware of the option for genetic testing

- Testing decisions are influenced primarily by providers and secondarily by insurance carriers

- Lack of insurance coverage may discourage providers from ordering genetic testing and by association may raise questions about their usefulness

The report also demonstrates inconsistencies when it comes to who makes the initial ASD diagnosis, who suggests or offers the genetic test (if at all), and the criteria used to determine a genetic test recommendation.

An ASD diagnosis can come from one of many types of providers across a variety of settings. In the Pathways study, initial diagnoses were made by either a single provider or a medical or diagnostic evaluation team made up of developmental pediatricians, neurologists, nurses, occupational and physical therapists, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and in one case, a dietician.

The most common setting was large specialty care centers. According to one provider from the study, “Most pediatricians aren’t going to make a diagnosis of autism. Most pediatricians, the vast majority, refer out to a tertiary center,” such as specialized autism centers or children’s hospitals.

Following an ASD diagnosis, families in the Pathways study typically were also offered a range of recommendations, community resources, and medical, educational, and behavioral therapies. But, here again, the amount and type of information they received — and from whom — varied dramatically.

Nearly a third of the families were not offered genetic testing at all, and others reported genetic testing as one among many options, but with no real guidance on what their next steps should be. When genetic testing was offered, it was rarely by the same provider who made the diagnosis. And when a genetic test was actually ordered, it was done by yet another provider.

As for the criteria for genetic testing, the majority of referrals were made based on whether autism ran in the family or if certain clinical features were present, such as abnormal growth or shape of certain body parts, seizure disorders, and severe developmental delays.

2. Which Genetic Test?

Current guidelines from such organizations as the American Academy of Neurology and Child Neurology Society, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Medical Genetics, and the International Standard Cytogenomic Array Consortium, illustrate the variations in recommendations that providers are exposed to, which adds to the confusion around the criteria for a genetic testing referral—and which genetic test to order.

According to several studies, including Heterogeneity in Clinical Sequencing Tests Marketed for Autism Spectrum Disorders, chromosomal microarray is currently the recommended first-tier genetic test for ASD. However, as the NFXF has previously reported:

Chromosomal microarray analysis is a powerful test for detecting certain genetic causes of developmental disabilities, but it is not able to detect Fragile X mutations of any kind.

The study also looked at the number and genes included in clinical gene sequencing panels offered by 21 commercial labs and marketed for autism spectrum disorders illustrates the need for health professionals to work toward a consensus: