Content was combined and adapted from original articles with help from numerous professionals within the FXCRC, including Brenda Finucane, Dr. Rebecca Shaffer, Jayne Dixon-Weber, and members of the NFXF team.

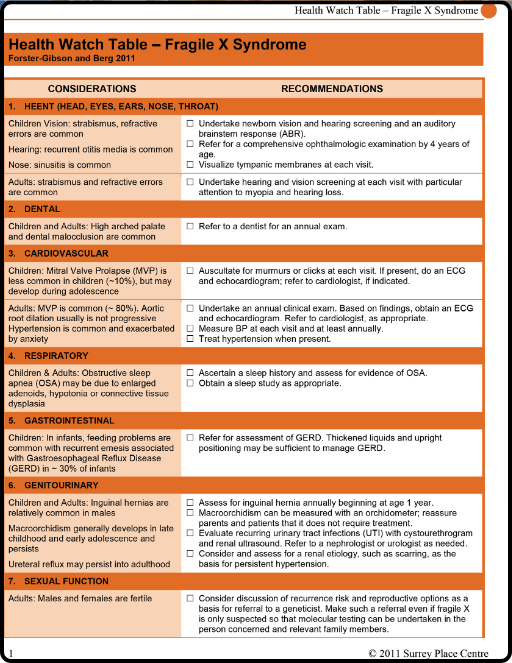

The effects of Fragile X syndrome are most noticeable in the cognitive behavioral domain (cognitive deficits, behavioral issues, and autism spectrum disorder). Multiple associated physical problems, mostly related to loose connective tissue, can also occur. These include hypotonia, hyperflexibility, flat feet, heart murmur, seizures, early puberty, and recurrent ear infections.

There is currently no definitive specific treatment for these physical problems. Management typically involves the combined efforts of a multidisciplinary team including ideally, psychology, developmental and behavioral pediatrics, neurology, speech and occupational therapy, neurology, psychiatry and genetics. Early diagnosis and early intervention is key to managing physical and medical concerns in FXS.

Individuals with FXS may have co-occurring diagnoses that impact physical and mental well-being, like ADHD or anxiety, for example. These can be symptoms of FXS, and they can also be their own diagnosis; therefore, it can be challenging to understand the root cause. Learn more about this from Brenda Finucane, a longtime genetic counselor and Fragile X champion: Making Sense of Multiple Diagnoses.

Because of the complexity of FXS, a multidisciplinary team is always encouraged to support your loved one with FXS. Curious about what that looks like? Learn more by watching our Multidisciplinary Treatment of Fragile X Syndrome webinar with Drs. Craig Erickson, Laura Hess, Kerrie Chitwood, and Rebecca Shaffer.

Common Medical Issues: Birth to Adulthood

Infants & Toddlers

Most infants with Fragile x syndrome are healthy and don’t require extensive medical intervention. There are some common medical conditions that can occur more often in babies with Fragile X syndrome.

Birth Defects

Babies with FXS have an increased chance of some congenital abnormalities such as cleft lip, cleft palate, clubfoot, congenital hip dislocation, and hernias. This may be related to loose connective tissue (more about this below).

Because these are all common birth defects among children without FXS, babies with these conditions are not routinely tested for FXS unless they present other symptoms, such as developmental delay, or a family history of Fragile x syndrome.

Low Muscle Tone

Many babies with FXS have hypotonia, which is low muscle tone. This is sometimes referred to as being “floppy,” which for a baby can cause difficulty in holding up their head, also known as “head lag.”

Because low muscle tone affects gross motor skills, such as sitting up or rolling over, hypotonia can contribute to the developmental delays often seen in babies and toddlers with FXS.

Digestive Disorders

Although many babies with FXS do well in the newborn period, others have difficulty with feeding, vomiting, or gastroesophageal reflux disease (known as GERD), a digestive disease in which stomach acid or bile irritates the lining of the esophagus (the tube connecting the mouth to the stomach).

This may be related to connective tissue abnormalities, low muscle tone (hypotonia), dysfunction of the gastroesophageal sphincter, or a hypersensitive gag reflex.

Some parents report that vomiting in babies with GERD can be resolved by positioning them upright during feeding and after meals. Occasionally, medication is needed to decrease reflux.

Babies will sometimes be diagnosed with what is called “failure to thrive.” This is typically related to difficulties in sucking, GERD, or an aversion to food textures. If feeding difficulties are a problem, particularly sucking or intolerance of certain food textures, consultation with an occupational or speech and language therapist, or therapies such as oral desensitization, oral stimulation, and oral motor coordination, can be helpful.

Ear & Sinus Infections

Beginning in the first year of life, frequent otitis media (middle ear infections) are a problem for many boys (and some girls) with FXS. In fact, the speech and language delays seen in children with FXS are often mistakenly attributed to chronic ear infections, sometimes delaying the Fragile X syndrome diagnosis.

Ear infections require treatment to avoid hearing loss that could further compromise language development. If a conductive hearing loss persists after acute antibiotic treatment, ear tubes (most commonly referred to as PE — pressure equalizing — tubes, but also known as tympanostomy or ventilating tubes) are often recommended.

Recurrent sinusitis (also referred to as sinus infection) is also a common problem in FXS, which may be related to the facial structure or the connective tissue problems that lead to recurrent ear infections.

Children and Adolescents

Urinary Tract Infections

Some children (more often boys), with FXS, may have an increased susceptibility to urinary tract infections and reflux (the backing up of urine into the urethra and bladder). The pediatrician may suspect an infection if the child has a fever of unknown origin with no other explanation, and thus a urine sample will be obtained.

Seizures

Approximately 20% of males and a smaller percentage of females with FXS have epilepsy. If your physician suspects your child is having seizures, often an EEG (electroencephalogram, which detects electrical activity in the brain) is performed. If seizures are confirmed, seizure medication is usually prescribed.

The largest and most definitive study yet published on seizures in FXS was completed using the Fragile X Online Registry with Accessible Research Database (FORWARD). A short summary of the study:

- Frequency: In this study, the overall chance of having at least one seizure was 12% overall in Fragile X syndrome, 13.7% in males, and 6.2% in females.

- Age of Onset and Resolution: In the group with seizures, the average age of the first seizure was 6.4 years of age with the great majority — 86.7% of males and 81.8% of females — having the first seizure before age 10. The age of the last seizure followed a similar age dependence to the age of the first seizure, with 70.9% of seizures in males and 63.6% of seizures in females resolving by age 10.

- Types: Partial (focal) seizures were reported in 25% and generalized seizures in 31% of those with seizures, with febrile seizures in 8% and the remainder of seizures being of unknown type. Males and females did not show a different distribution of seizure types.

- Association of Seizures with Other Fragile X Syndrome Characteristics: As compared to individuals with FXS without seizures in FORWARD, those with seizures were more likely to have more severe intellectual disability, current sleep apnea, delayed acquisition of expressive language, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), hyperactivity, irritability, and stereotyped movements.

- Treatment and Medications: Treatment and management of seizures in Fragile X syndrome is similar to seizure treatment in other conditions associated with seizures. There is no Fragile X syndrome-specific medication or approach to treating seizures. A person with seizures is usually treated with medications, known as anticonvulsants, after two (or sometimes more if there is a long time between seizures) seizures.

Seizures are reported to be easily controlled in most cases and have been thought to resolve during childhood in the majority of individuals with FXS.

From our consensus-based treatment recommendations, a deeper look at seizures related to Fragile X syndrome:

Seizures in Fragile X Syndrome

Based on study data, 12% of people with Fragile X syndrome have seizures, and treatment and management are similar to seizure treatment in other conditions associated with seizures. They are easily controlled in Fragile X syndrome and most patients grow out of their seizures before their 20s.

Physical Problems in Fragile X Syndrome

Multiple associated physical problems can occur with FXS, mostly related to loose connective tissue.

Eye Disorders

Children with Fragile X syndrome have an increased susceptibility for vision and eye disorders, which are common in childhood.

These include:

- Strabismus: Also called “lazy eye,” this condition causes the eye to appear “crossed” or drifting to the middle. This is often due to low muscle tone in the eye, a symptom of the hypotonia present in many babies or children with Fragile X syndrome.

- Ptosis: Drooping of the eyelid, again often related to low muscle tone.

- Nystagmus: Shaking of the iris in a back and forth motion.

- Myopia/Hyperopia: Subtle near- or farsightedness.

It is recommended that all children with Fragile X syndrome be referred to an ophthalmologist if the pediatrician suspects any of these common eye or vision conditions.

Connective Tissue Issues

Connective tissue is the tissue that holds together the body such as skin, muscles, tendons, cartilage, ligaments, bones, and blood vessels. Many individuals with Fragile X syndrome have differences in their connective tissue. Some of these connective tissue problems include:

- Scoliosis: Curvature of the spine, usually not severe.

- Flat feet: Also called pes planus.

- Hernias: Inguinal (groin) hernias.

- Cardiac murmur: Often a functional or innocent murmur, it is sometimes indicative of mitral valve prolapse (or MVP, which is improper closure of the valve between the heart’s upper and lower left chambers.). Occasionally an evaluation by a cardiologist is warranted to confirm MVP, and if confirmed, the cardiologist may recommend antibiotics prior to dental procedures or surgery.

- Hyperflexible joints: Particularly of the wrists, fingers, and elbows.

- Soft skin

- Macroorchidism: Testicular volume normally increases during the early stages of puberty, but in boys with Fragile X syndrome this increase is usually quite dramatic, leading to macroorchidism (enlarged testicles). These changes are typical for Fragile X syndrome, and do not require intervention. Some boys with Fragile X syndrome develop large testicles prior to the onset of puberty.

Adults

Sometimes what are seen as behavioral or emotional challenges in individuals with FXS may have an underlying medical cause; this is one of the reasons why having a primary care physician is so helpful. It can be helpful to seek an opinion from a doctor to exclude a medical cause of any changes in behavior, especially if it persists.

You can find more information and a list of medical problems associated with Fragile X in the NFXF treatment recommendation, Transition to Adult Services for Individuals with Fragile X Syndrome:

Transition to Adult Services for Individuals with Fragile X Syndrome

There are many new issues to address as an individual with FXS becomes an adult. Services can vary widely from state to state and even vary within a state, so it is up to the parents or providers to find what is available and to set up the daily schedule for or with the person with FXS.

Mental Health Throughout the Lifespan

Mental health contributes to our overall wellbeing. Mental health can impact our thoughts, feelings and actions. This then impacts how we interact with the world and others, make decisions, and handle stressors. Emotional, psychological, and social wellbeing are all parts of mental health.

Challenges with mental health are most prominent in adolescents and adults with FXS. It is important to seek out professional help and support for any mental health concerns. Learning strategies to support emotion regulation can be incredibly helpful.

Learning more about behaviors in FXS may also help. Visit our FXS topic page Managing Behaviors plus two webinars presented below.

Mental Health Webinars

Multidisciplinary Treatment of FXS

Emotional Regulation in Fragile X Syndrome

Find a Fragile X Clinic

Fragile X clinics provide medical services -including medication evaluations and consultations- supervised by a physician and supported by the latest medical, educational, and research knowledge available. Multidisciplinary services, such as genetic counseling and occupational, speech, language, and behavioral therapies, are also available either at the clinic or by referral.

- Find a U.S. Fragile X Clinic

- Find Clinics Specializing in the Treatment of FXTAS

- Find an International Clinic

Preparing for an In-Person Clinic Visit

Preparing for an in-person visit to a Fragile X clinic can set up you and your loved on with FXS for success. The clinic can help you prepare too, so be sure to ask about any materials they have on hand about what to expect. Don’t forget to bring comfort items and activities for you and your loved one; headphones can be especially helpful in waiting rooms! Don’t be afraid to ask for accommodations if you need them. And don’t be afraid to ask any and all questions you have — the clinics have heard it all and are there to help.

Preparing for a Telehealth Visit

Many NFXF Fragile X Clinical & Research Consortium clinics offer telehealth visits in addition to in-person. Note there are specific parameters to these visits, and they vary from clinic to clinic and state to state. We have gathered information to help you make the most of your online telehealth visit to a Fragile X clinic.

Learn more about Telehealth Visits: Suggestions for Parents on How to Prepare

Medications

Medications are at times helpful to facilitate the individual’s ability to attain optimal life skills and allow for better integration into educational, adult, and social environments.

Our treatment recommendation and consensus of the Fragile X Clinical & Research Consortium provide the most current guidance.

Medications for Individuals with Fragile X Syndrome

Medications are, at times, helpful to facilitate the individual’s ability to attain optimal life skills and allow for better integration into educational, adult, and social environments.

Non-Medication Treatments & Therapeutic Interventions

Non-medication treatments and therapeutic interventions may be used in addition to medications or on their own. When a medication is recommended to help address symptoms or specific behaviors, it may be recommended in combination with other therapeutic interventions. Examples of these interventions are behavioral, cognitive, developmental, vocational, and educational therapies.

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

The Use of Complementary and Alternative Therapies in the Treatment of Fragile X Syndrome

If a family is considering complementary, alternative, or integrative therapies, we strongly recommend that they review the treatment under consideration with the physician in charge of managing the child’s FXS symptoms.

Additional Resources

Related Medications Webinars

July 17, 2025

01 h 02 m

February 21, 2024

00 h 37 m

July 17, 2022

01 h 04 m