NFXF Blog

Featured

Congratulations to 2025’s three NFXF Summer Scholars. Meet Susana Lopez-Ignacio, Tanvi Kamra, and Shelby Dauterman!

‘Fishing for a Cureʼ Reels in Over $20,000 This Year!

12 mins read

FORE! Fragile X Annual Golf Event Raises over $63,000 (So Far!)

05 mins read

Mirum Launches Phase 2 Trial of MRM-3379 for Fragile X Syndrome

03 mins read

Relationship Between Intellectual Disability and Behavioral Comorbidity in Children with Fragile X Syndrome

03 mins read

All Articles

We’re thrilled to spotlight a major new review article recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) – The Spectrum of Fragile X Disorders by Randi J. Hagerman and Paul J. Hagerman.

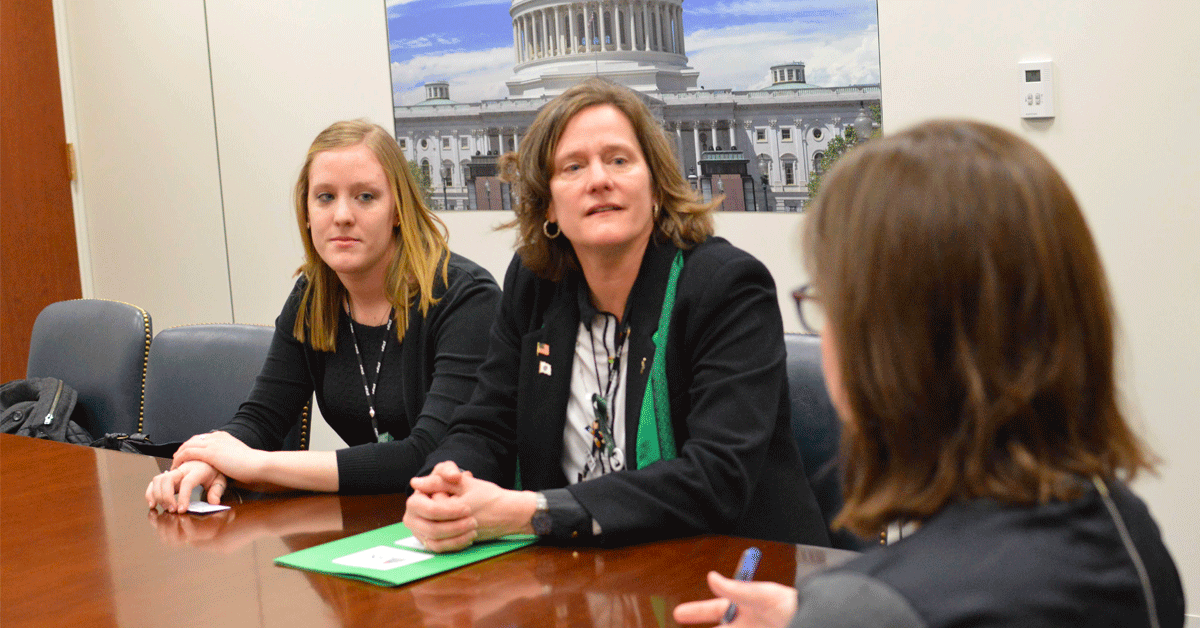

We are seeing numerous proposed changes this Congress that would have a significant impact on the Fragile X community. It’s more important than ever that your members of Congress hear directly from you — your voice matters.

We understand the uncertainty surrounding recent developments, especially potential changes to federal funding that could impact the Fragile X community. We closely monitor the situation and continue working with our strategic partners to stay informed.

We know many individuals living with Fragile X want to work, and though some do, not everyone who wants a job has found one that best fits their strengths and skill sets. We’re determined to help you educate yourself on the existing supports and how to best advocate in the workplace.

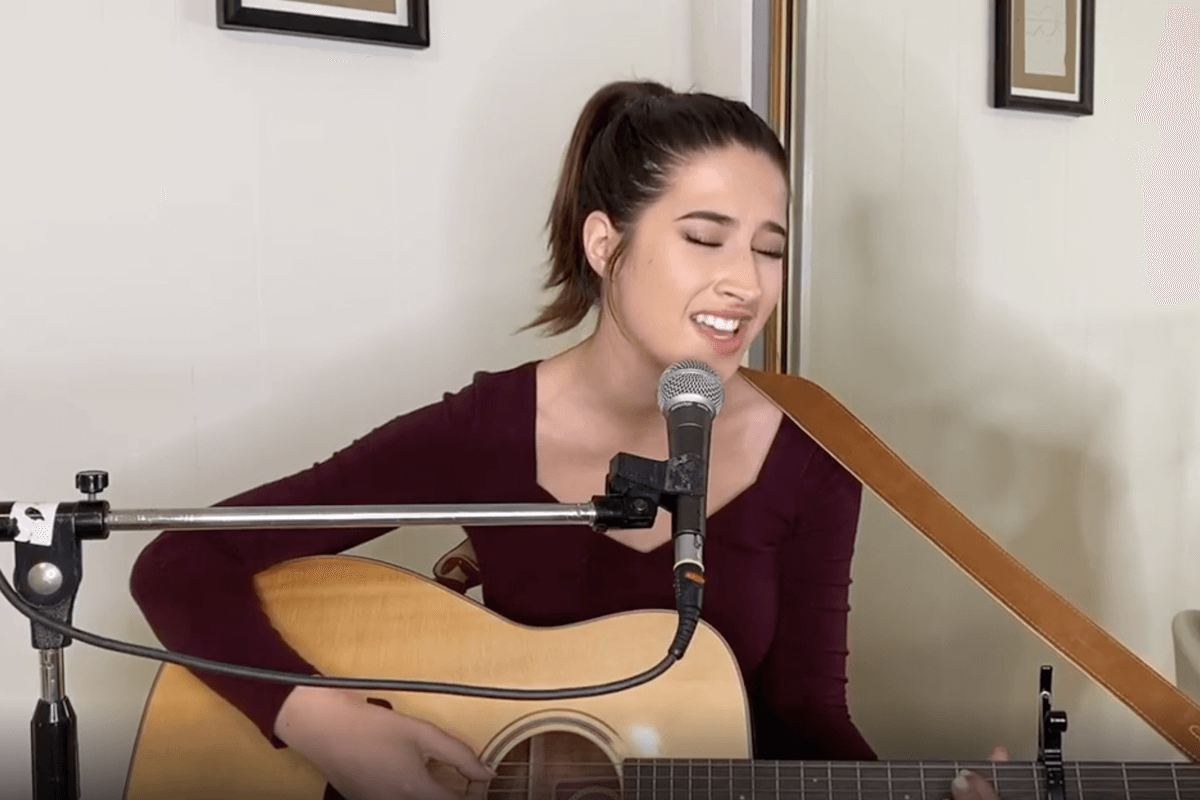

American Idol featured Sophia’s relationship with her brother James, who has Fragile X syndrome. The show reached 8.05 million viewers.