General Seizure Information

What is a Seizure?

A seizure is a single event characterized by an abrupt change in behavior (e.g., staring without response, dropping to the ground, or twitching a part or all of the body). What you don’t see is that the behavior is accompanied by a burst of electrical discharges that comes from neurons in the brain, i.e., the behavior appears in association with the burst and then goes away when the burst is over. A seizure occurs either as primary excess electrical excitability in an otherwise normal brain or secondary to another disorder. In Fragile X syndrome (FXS) the excess electrical excitability is most likely related to the effects of the genetic change in the Fragile X gene (FMR1) and the resultant loss or reduction of the Fragile X protein (FMRP) on activity in neurons.

Other causes of seizures have to be considered in a person with Fragile X syndrome as there could be another diagnosis in addition to the FMR1 gene mutation. These causes include:

- An acute response to a new condition (such as trauma, infection, stroke, toxin/drug, tumor, metabolic problem)

- A delayed effect due to a recent disease (trauma, infection, surgery)

- A permanent brain “scar” from an old disease (stroke, prenatal or perinatal insult, tumor, infection)

A seizure refers to the event that occurred. A person is said to have epilepsy when they have had recurrent (at least two) seizures.

Classification of Seizures

Seizures are classified according to the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) Classification of the Epilepsies.

Focal Seizures (aka Partial Seizures)

Focal onset seizures are seizures starting on one side or in one area of the brain. These are divided into focal aware seizures, in which the person is awake but having a localized seizure manifestation (like an arm twitching), and focal seizures with impaired awareness, in which there is an alteration of consciousness (also commonly referred to as complex partial seizures, or CPS). A focal seizure can spread to the entire brain and “generalize,” becoming a focal to bilateral seizure. Focal seizures may signify a problem in a specific area of the brain or may occur as part of a genetic syndrome without a specific area of the brain being abnormal.

Generalized Seizures

Generalized seizures involve both sides of the brain all at once. These include generalized motor seizures, which can be:

- Tonic-clonic: Stiffening followed by jerking

- Tonic: Stiffening

- Clonic: Jerking

- Myoclonic: Single or clusters of jerks

- Atonic: Sudden loss of tone — head drops, falls

- Absence or generalized non-motor seizures: Staring, eye blinking

Generalized tonic-clonic (GTC) seizures (known in the past as “grand mal”) are the most well-known seizure type and occur instantly, sometimes associated with a loud cry at the onset. Typically, the eyes open and roll up, and there may be noisy breathing, jaw clenching, oral secretions pooling in the mouth, stiffening and jerking throughout the body, incontinence, and drowsiness after the seizure is over.

Status Epilepticus Seizures

Status epilepticus is a single or repeated seizure lasting more than 30 minutes. This may be associated with poor breathing effort (shallow breathing), increased blood pressure, pulse, and temperature.

Febrile Seizures

Febrile seizures are a specific kind of short, generalized seizure occurring only with fever in children aged 6 months to 5 years. A range of 2%-5% of typical children have these, so they are very common in the population and they go away by age 6. As this type of seizure is so common, there will of course be individuals with Fragile X syndrome who have febrile seizures, but it is not thought these are increased in Fragile X syndrome.

Evaluation of Seizures

In the evaluation of seizures, it is important to collect a detailed moment-by-moment history of the event, including:

- Activity

- Body position

- Progression

- Duration

- Loss of sphincter tone, resulting in urination or a bowel movement

- Tongue biting

- Visual, auditory, or olfactory auras

This will help determine if the event was likely an epileptic seizure versus a non-epileptic spell that might include things like:

- Shuddering

- Breath-holding

- Benign nocturnal myoclonus (twitching when falling asleep)

- Night terrors

- Migraine

- Panic attack

- Fainting

- Hyperventilation

- Heart arrhythmia

Initial seizures are usually evaluated with a laboratory evaluation that might include glucose, electrolytes, and calcium, and if the seizure seems like a focal seizure, an MRI would be obtained. An elevated prolactin level can also verify a recent seizure. A spinal tap may be needed to rule out infection if there is fever or an extended change in responsiveness beyond the seizure. An EEG (electroencephalogram) is usually done two weeks after the seizure to look for abnormal discharges and determine their location and character.

Typically, patients would be referred to neurology to manage seizures although in uncomplicated cases the primary care physician may handle the problem. Referral to neurology should always be done when there is confusion over:

- Whether the person is definitely having seizures

- The cause of the seizures

Or if:

- There is poor response to single drug treatment

- The physician is uncomfortable with seizure treatment

- The family is anxious about management options

- The patient has a complex mix of problems — e.g., behavior, learning disability, seizures — that may involve a specialized approach

Use of EEG

The EEG is used in people with seizures to:

- Diagnose the type of epilepsy

- Determine if episodes are actually seizures

- Identify epilepsy syndromes

- Help guide treatment decisions

After a major seizure there may be slowing of the brain activity and suppression of seizure foci so because the EEG may miss seizure activity, it is better to get the EEG two weeks after a major seizure. Ambulatory EEG (an EEG that a person wears for one or more days at home, such as Neurotech and DigiTrace) is used to monitor spells that may or may not be seizures so that the correct diagnosis can be made.

It is important to recognize that while a routine EEG is indicated to help guide treatment for a person suspected of seizure disorder, it may not be diagnostic, which means one has to rely on clinical judgement. Many individuals with FXS and seizure disorder have an abnormal EEG characterized by focal spikes or sharp discharges, however, those with FXS who will never have seizures may also have this or other abnormal EEG patterns. Individuals with FXS and seizure disorder may show other abnormalities on an EEG, or no abnormalities at all.

Thus, the EEG is not a useful test for individuals with FXS who do not have clinical episodes concerning seizures, because it does not predict who will develop clinical seizures.

Seizures in Fragile X Syndrome

There have been multiple reports in medical journals describing seizures in FXS and those reports studying the larger groups have identified seizures in 4.4%-18% of individuals with FXS.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] Many children with FXS also have abnormal EEGs without overt epileptic seizures.[3, 5, 7] When seizures do occur, both focal and generalized types of seizures are seen. Seizures are reported to be easily controlled in most cases and have been thought to resolve during childhood in the majority of individuals with FXS.[3, 6, 7]

Frequency of Seizures in Fragile X Syndrome

Recently, the largest and most definitive study yet published on seizures in FXS was completed using FORWARD (Fragile X online registry with accessible research database) a multisite observational study initiated in 2012 involving participants seen at Fragile X syndrome clinics in the Fragile X Clinic and Research Consortium.[8] The study analyzed data on seizures collected longitudinally every year for multiple years of time from 1,607 participants with FXS. In this study the overall chance of having at least one seizure was 12% overall in FXS, 13.7% in males and 6.2% in females.

Age of Onset and Resolution of Seizures in FXS

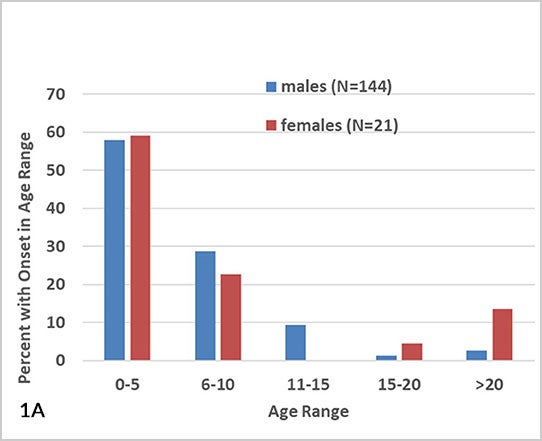

In the group with seizures, the average age of the first seizure was 6.4 years with the great majority (86.7% of males and 81.8% of females) having the first seizure before age 10 years (see Fig.1A).

- For males, 96% had the first seizure by age 15, meaning that only 4% of those with seizures (0.5% or 1 in 200 of all males with FXS) had a first seizure after age 15.

- For females with seizures, 18.2% (1% of all females with FXS) had their first seizure after age 15.

The age of the last seizure followed a similar age dependence to age of first seizure, with 70.9% of seizures in males and 63.6% of seizures in females resolving by age 10 (see Fig. 1B). Only 7.9% of males and 18.2% of females (1% or 1 in 100 of all males and females with FXS) still had seizures continuing after age 20.

New onset seizures occurred in participants in FORWARD at a rate of 0.013 new seizures per person, per year of follow up, meaning about a 1 in 100 chance of having a first seizure each year for those in follow-up. Seizures changed type, for instance, a person with generalized seizures began to have focal seizures in about 4.2% of males with FXS, and seizures each year of follow-up.

Figure 1A-B: Age of Onset and Resolution of Seizures in Fragile X Syndrome

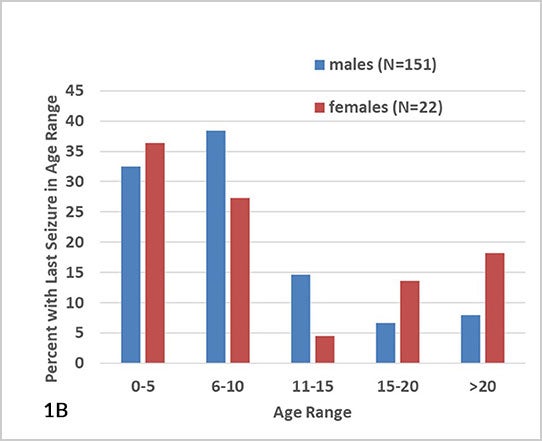

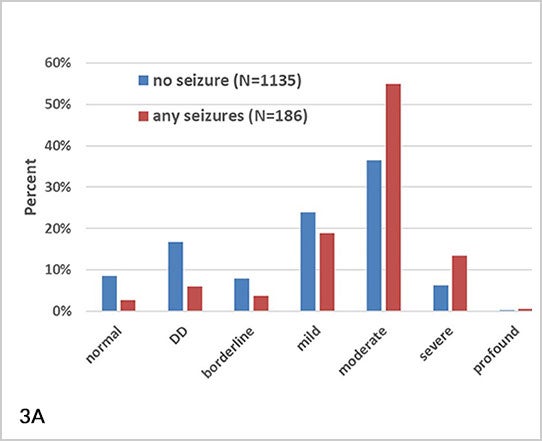

Types of Seizures in Fragile X Syndrome

Partial (focal) seizures were reported in 25% and generalized seizures in 31% of those with seizures, with febrile seizures in 8% and the remainder of seizures being of unknown type (see Fig. 2).[8] Males and females did not show a different distribution of seizure types.

Figure 2: Seizure Types in Fragile X Syndrome

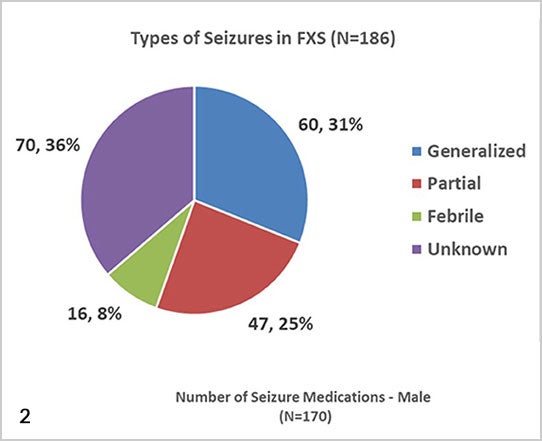

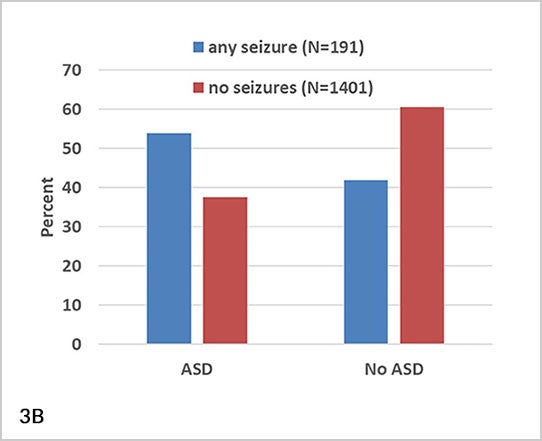

Association of Seizures with Other Fragile X Syndrome Characteristics

As compared to individuals with FXS without seizures in FORWARD, those with seizures were more likely to have more severe intellectual disability (see Fig. 3A), current sleep apnea, delayed acquisition of expressive language, autism spectrum disorder (see Fig. 3B), hyperactivity, irritability, and stereotyped movements.[8] The association with ASD confirmed findings from several prior studies suggesting an association of seizures with ASD in FXS.[9, 10, 11] For those with FXS and epilepsy, about half (52%) had seizures for more than three years. This group was found to have greater cognitive and language impairment, but not behavioral disruptions, compared with those with seizures for less than three years.

Figure 3A-B: Association Between Intellectual Disability, Autism Spectrum Disorder, and Seizures in Fragile X Syndrome

Treatment of Seizures in the General Population and in Fragile X Syndrome

Treatment and management of seizures in FXS is similar to seizure treatment in other conditions associated with seizures. There is no FXS-specific medication or approach to treating seizures.

First Aid

If a person has a seizure, standard seizure first aid should include the following:

- Remain calm

- Put the person on their side

- Make sure the person is breathing, and monitor as the episode runs its course

- Do not put anything in the person’s mouth, including food or drink

- After the episode, let the person sleep if needed

If at any time during the episode the person turns blue or stops breathing, or if the seizure lasts more than 5 minutes, call the paramedics. Consider giving rescue medication (such as rectal diazepam [Diastat] or intranasal midazolam) if the seizure lasts over 3-5 minutes.

If the seizure is the first lifetime event, the person should be brought to medical care for testing for the underlying cause.

Status epilepticus is defined as a single seizure that lasts for at least 30 minutes without the person becoming alert and responsive, or back-to-back seizures without return to baseline in between. Status epilepticus is a medical emergency requiring assessment and treatment in an emergency room setting, appropriate airway management, laboratory investigations, intravenous anti-seizure medications, and intubation or ventilation in the setting of respiratory compromise.

Medications for Use in Fragile X Syndrome

A person with seizures is usually treated with medications, known as anticonvulsants, after two seizures (or sometimes more if there is a long time between seizures).

To select a medication:

- It is important to consider the patient characteristics and try to use a single drug regimen at the lowest effective dose.

- The guide to dosing is typically effectiveness, and side effects and blood levels are less important.

- An EEG can be used to help decide which drug to use, how much, and how long.

- More drug is not necessarily more effective.

- Anticonvulsants with good side effect profiles that are commonly used initially for seizures are Keppra (levetiracetam) and Trileptal (oxcarbazepine), but other medications may be needed if these are not effective or have side effects.

The following list shows available anticonvulsants, seizure types for which they are used, and the side effect profile.

Anticonvulsants

Medications most reasonable as first line choices for FXS: Choose based on behavioral issues in the individual and the EEG pattern, in consultation with a neurologist. Note: Medications most commonly used in FXS are lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine, shown below in blue.

| Drug | Main Treatment Focus and Side Effects |

|---|---|

| Brivaracetam | Partial seizures; similar to levetiracetam but may have less behavior side effects |

| Cannabidiol (CBD) | Epidiolex is an FDA-approved form of CBD for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome seizures; over-the-counter CBD should be used in consultation with a neurologist |

| Carbamazepine | All seizure types, particularly partial; can cause marrow suppression, liver toxicity, needs blood monitoring |

| Cenobate | Partial and generalized seizures |

| Clobazam | Partial and generalized seizures, less risk of tolerance compared with other benzodiazepines |

| Clonazepam | Partial and generalized seizures, general given only for a short time as a bridge to another antiseizure medication |

| Felbamate | Partial seizures; can cause bone marrow and liver toxic, needs blood monitoring |

| Fosphenytoin | Given IV for status epilepticus; has less toxicity than phenytoin, the pro-drug |

| Gabapentin | Partial seizures; easy add-on medication |

| Lacosamide | Partial and generalized seizures; favorable side effect profile |

| Lamotrigine* | Partial and generalized seizures; slow titration to therapeutic dose to avoid Stevens-Johnson syndrome (severe allergic skin rash), low rate of cognitive side effects |

| Levetiracetam* | All seizure types; low rate of side effects and interaction with other drugs, may aggravate behavior, which can be ameliorated in some cases with vitamin B6 co-treatment |

| Oxcarbazepine* | Partial seizures, can also be used for generalized tonic-clonic seizures |

| Perampanel | All seizure types; can cause psychiatric side effects (psychosis) and sedation |

| Phenobarbital | Older medication, all seizure types; not used often due to sedation and cognitive depression |

| Phenytoin | Older medication, all seizure types; not first line choice due to gingival hypertrophy, cerebellar effects, facial coarsening |

| Rufinamide | Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (multiple seizure types and characteristic EEG) |

| Tiagabine | Partial seizures |

| Topiramate | All seizure types; can cause weight loss, language impairment, kidney stones |

| Valproic acid | All seizure types; can cause weight gain, hair loss, low platelets, liver toxicity, needs blood monitoring |

| Vigabatrin | Partial seizures, infantile spasms; can cause peripheral visual field constriction |

| Zonisamide | Partial seizures |

Diet

The ketogenic (or keto) diet can also be used for seizure control. The classic ketogenic diet is a high fat, low carbohydrate diet in which 90% of calories come from fat. This diet causes ketosis, which is associated with seizure control.

The diet produces improvement in about 20% of people with intractable seizures and is typically used when multiple anticonvulsants fail or when there are problems with anticonvulsant side effects. The diet works best in children under age 4, and the family and child must be motivated to follow the diet and avoid cheating. The diet works best for atonic (sudden loss of tone — head drops, falls) and absence (staring, eye blinking) seizures but can work for all seizure types.

Vagal Nerve Stimulator

The vagal nerve stimulator, or VNS, can be used to control seizures. It is a small device implanted by surgery at the base of the neck on the vagal nerve and is then set to stimulate the nerve at a certain frequency. The frequency of stimulation can then be adjusted to give the best seizure control.

The VNS achieves a substantial improvement in seizure control in about 10% of those with difficult-to-control seizures. It works best when the person has anauraand can activate the device to abort a full seizure.

Risks of VNS placement include hoarseness after surgery and infection around the device.

Surgery

Epilepsy surgery is an option for patients with very difficult-to-control focal seizures coming from one part of the brain. It can sometimes be used in a disorder affecting the entire brain if the seizures are uncontrolled and there is one area from which most seizures seem to arise.

Breakthrough Seizures, Epilepsy Care and Stopping Anticonvulsants

When on treatment, breakthrough seizures may occur associated with non-compliance (inconsistent use) with medications, too little sleep, illnesses and fever, and possibly stress, or for no reason. When there are ongoing seizures without an obvious reason (e.g,. missed medication doses), the medicine can be increased, changed, or medication can be added. When there is frequent recurrence with prolonged seizures or clusters of seizures, rectal valium (Diastat) or nasal midazolam (Nayzilam) can be used to stop seizures and avoid frequent emergency room visits.

Total epilepsy care should include medication for seizure control with adjustments for side effects and if needed, psychosocial support, educational recommendations and accommodations, behavioral management, and vocational counseling.

If an individual is on a seizure medication, it is helpful to share this information with therapists and school or program teams and to include information on the possible side effects, as these may be a factor for intervention planning and it will be important for all of those working with the person to be aware of all factors related to the seizure treatment.

Seizure medications can be stopped after being two years seizure-free, especially if the EEG is normal. Longer treatment may be recommended if the person has an underlying condition associated with significant seizure risk or if the EEG still shows strong epileptic activity. If a patient is on multiple medications, typically one at a time would be weaned after the person is seizure-free for a year or two. There is always some risk of recurrence no matter how long weaning is delayed past two years seizure-free, but the risk does not really change after two years. Medication can be restarted if seizures recur after weaning.

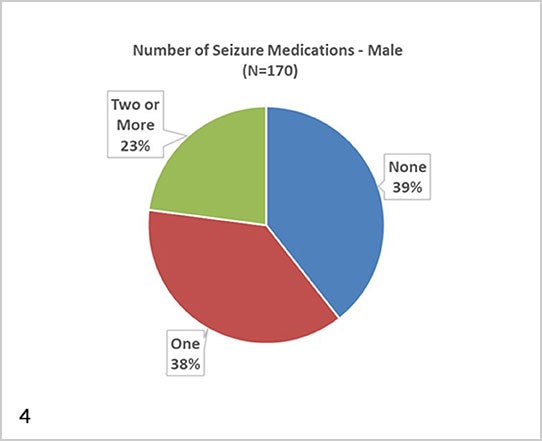

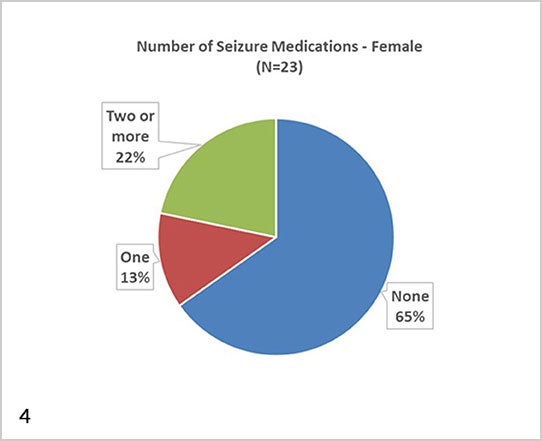

Data on the Treatment of Seizures in FXS

Based on the large study from the CDC-funded FORWARD project some information in known about how many individuals with FXS and seizures were on medication for seizures during their time in follow up through the FORWARD project.[8] In this study, antiepileptic drugs were more often used in males (60.6%) than females (34.8%) and females more often required more than one medication (see Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Anticonvulsant Use in Fragile X Syndrome

When individuals with FXS and seizures were not taking medication, it was largely because their seizures had resolved when seen in FORWARD or they only had one or a few very infrequent seizures.

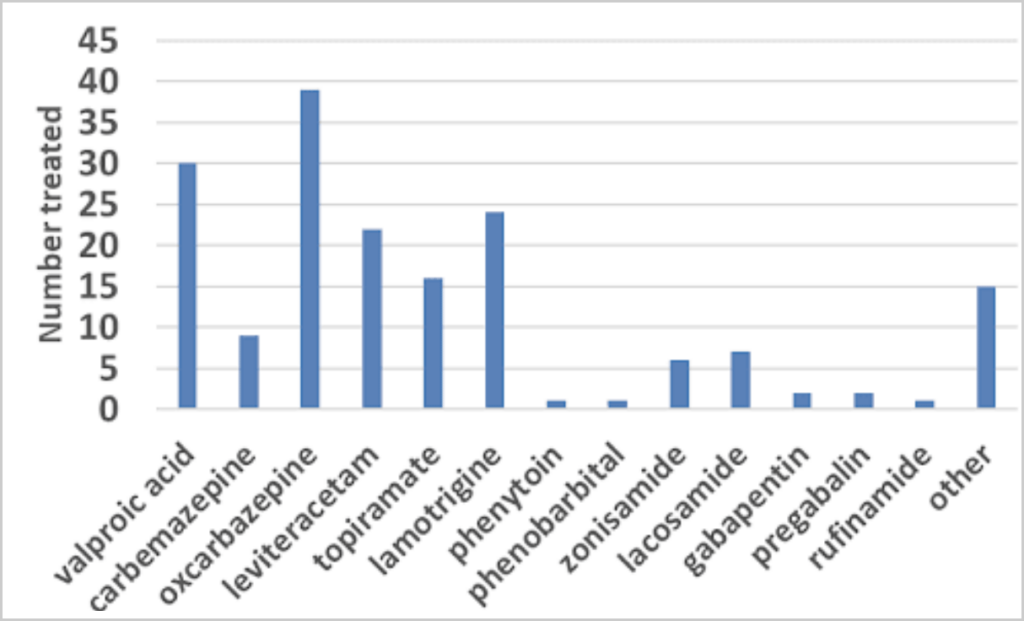

First-Line Choices in Fragile X Syndrome: While a discussion of the pros and cons of all the various anticonvulsants is beyond the scope of this document, oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), levetiracetam (Keppra), and lamotrigine (Lamictal) are medications with relatively good profiles in terms of cognitive side effects that do not require standard blood monitoring in children, and thus may be viewed as first-line choices in FXS.

The FORWARD Study: The most commonly used anticonvulsant was oxcarbazepine, followed by valproic acid, lamotrigine, and levetiracetam (see Fig. 5). Levetiracetam, although the first line drug for seizures in children in the U.S., was not most commonly used in FXS due to concerns about aggravation of behavior. Although this is a concern, it does not contra-indicate use of levetiracetam in FXS, as only 15% of those started on the drug experience worse behavior and B6 can ameliorate behavioral issues.

Valproic acid may be good for certain EEG patterns and when there are seizures and mood-aggression or language regression issues; it may also be effective in cases where seizures are not responsive to the first-line medications.

Medications That Are Not First-Line Choice

Phenobarbital is generally avoided, and gabapentin, clobazam, clonazepam, and perampanel are not first-line choices because of their tendency to worsen hyperactivity and other behavioral issues. Phenytoin is typically avoided due to facial coarsening, acne, and other undesired effects on appearance with long-term use in children.

Figure 5: Use of Specific Anticonvulsants in Fragile X Syndrome

Conclusion

In summary, based on the FORWARD data, 12% of people with FXS have seizures. Treatment and management of seizures in FXS are similar to seizure treatment in other conditions associated with seizures.

There is no FXS-specific medication or approach to treating seizures, but the approach is to try to use the medications expected to have the least side effects first and those not requiring blood monitoring. In general, seizures are easily controlled in FXS and most patients grow out of their seizures before their 20s although, infrequently, seizures can be a more challenging problem.

Frequently Asked Questions

My patient isn’t having any seizure-like symptoms, but his family would like me to do an EEG anyway. Is this necessary?

The EEG is generally used to provide data to support or detract from a clinical suspicion. As discussed above, however, many nonepileptic individuals with FXS have striking abnormalities on EEG, while some individuals with seizures and FXS may have mild or no abnormalities on this study. Because of this the EEG is not helpful in evaluating individuals with FXS and no clinical symptoms of seizures. If your patient is having a significant unexplained change in sleep habits, decline in communication skills, or dramatic increase in aggression, it may be appropriate to order an EEG even though these symptoms are not typically epileptic.

My patient’s teacher is reporting that she “stares into space” frequently and does not respond when her name is called. The teacher has to touch the child’s shoulder to get her attention. The staring lasts for several minutes and does not seem to be associated with any focal motor symptoms. The parents, who have never seen these spells at home, know about the association between Fragile X syndrome and seizures and are concerned.

Although staring and inattentive episodes are universal in students, they are more common in children with ADHD and intellectual disabilities. They may be more likely in less stimulating environments or when the child is overwhelmed or fatigued. The parents’ description of these episodes is not highly concerning for seizure, as the child becomes alert when they are touched. In addition, the symptoms seem dependent on environment, whereas seizures tend to occur across environments.

Additional Resources

Seizures and Epilepsy in Childhood: A Guide

A family-friendly book reviewing the medical and psychological issues related to seizures. By John M. Freeman, MD; Eileen P. G. Vining, MD; Diana J. Pillas (Johns Hopkins University Press).