“Siri, what does the fox say?” we asked our personal assistant.

“Siri, what does the fox say?” we asked our personal assistant.

“Ding ding ding da ding da ding ding.”

“Siri, what is Fragile X syndrome?”

“I’m checking … here’s what I found.”

Siri then provides information from the Wikipedia site definition of Fragile X , the NIH genetics home reference page on Fragile X , and the MedicineNet page on Fragile X syndrome.

Siri-ously – good information is readily available! Here on the National Fragile X Foundation site, there are PAGES and PAGES of credible, helpful information. We often remind fellow interventionists and educators time and time again about the many unique aspects of Fragile X syndrome as well as the resources available online and in print.

The Fragile X Learning Style

The specific phenotype of Fragile X syndrome results in a particular way of thinking, what we call the Fragile X learning style. It also phenotypically results in a presentation of anxiety and hyperarousal. These key aspects of Fragile X syndrome must always be at the forefront of our minds to guide any educational, therapeutic, behavioral, vocational, or independent living plan. In fact, if you ask Siri about either of these, information is readily available with links to this website, including treatment recommendations and research.

Our new global ability to access information lends hope that interventionists and educators as well as families and medical providers can be more informed. Fragile X syndrome and its nuances no longer need to be a mystery. Just ask Siri!

Below are two recent and not uncommon scenarios that recently came to us by email. These examples highlight that accessing Fragile X syndrome–specific information is essential to good programming. Families raising a child or an adult with Fragile X are encouraged to understand and advocate for programming that includes an understanding of the key aspects of Fragile X syndrome.

From one resource:

An FBA (Functional Behavioral Assessment) is provided for a student with FXS who presents inappropriate behavior (you name the BEHAVIOR — avoidance, aggressions, silliness to gain attention, escaping, no engagement with non-preferred activities, etc. ). Fancy charts of data may accompany the FBA, linking the behavior to the motivation. The function of the behavior is identified (one of seven common functions, though none of them are FX-specific) and a plan is put in place to support and reinforce the desired outcome. However, even a well-trained behaviorist may miss the common FXS-specific reasons (or antecedents) for the behavior, rendering the assessment just off track enough to not effectively guide intervention. For instance, we recently reviewed a behavior plan that was not working well for an elementary-aged boy with FXS. The intervention included the use of a token economy and reinforcers for desired compliant behavior to be faded out when his inappropriate behavior was reduced by 80%.

In the above example, there was no mention of the child’s learning strengths, interests, or how his learning style would be addressed. We know that when a child’s learning style is not met, slower learning and an increase in maladaptation will likely result.

Additionally, there was no mention of the effect of the Fragile X biology on hyperarousal (a common behavioral antecedent) and no proactive plan included to manage the antecedent. It is not a mystery, then, that the plan was ineffective.

Unless the true reason for the behavior is identified and managed by a comprehensive, positive behavioral support plan, the plan will not work. In the scenario just described, the assessment and resultant intervention plan would have hit the mark if it simply had included the basic information on hyperarousal and the basic learning style common to Fragile X syndrome.

Let’s consider another common theme:

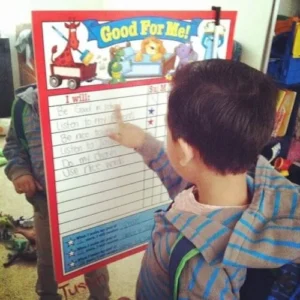

After two years in the same classroom, a seven-year-old is starting to be placed part-time in the regular education classroom, as part of a transition for next year’s halftime resource room, halftime special education. His special education teacher has stopped using any visual supports because the child is “doing so well.” The child is now showing avoidant and disruptive behaviors all day long, previously unusual for him, and the teacher is asking what to do.

We frequently hear about a teacher that used to use visual supports but faded them out because a child was doing so well. This leads to the “things are falling apart” 911 call to us four or five months later.

Living with Fragile X means learning to live with ongoing strategies and support. It is akin to an insulin-dependent diabetic — no one would question the need for wellness and medical support in such a person and the goal would not be to suddenly stop taking insulin because the person is doing so well.

We know that individuals with Fragile X syndrome are visual learners. This will not change — even when they have excellent comprehension of verbal information and understand the routines of the day.

The visual approach is important for specific learning, but more than this, visual supports are important as they “hold” information for the person in an external place, freeing up thinking space and reducing anxiety.

Visuals:

- Function as an ongoing means of keeping hyperarousal in check

- May be used to help with transitions during the school day. The visuals allow for consistent and reliable safety support so that when a more challenging transition is impending, the child can rely on the visuals to help them in that situation.

- Offer a ready means of keeping directions and demands a bit more indirect. As indirect interaction helps to limit social anxiety, a visual acts as an intermediary between the person of authority and the individual, and therein is an important tool.

Fading support is just not an option. The nature of the support may change — a visual picture schedule at age eight may turn into an iPhone calendar app at age 23. Learning to use — even embrace — visual supports is the goal, not fading them out due to progress.

So, whether observing for a functional behavioral assessment or transitioning a child into a new class, we must always remember to take into account how the specific phenotype of Fragile X syndrome affects our programming.

We at the NFXF have an abundance of material available for free to help us make informed decisions about how to support our children and adults with Fragile X syndrome, and this information is readily available, just ask Siri!